This blog follows on from Part 1 which introduced the Island’s population imbalances as highlighted by the 2021 Census. Given these imbalances, and the direction of travel, the need for intervention to ensure that the population the Isle of Man is sustainable is apparent. Part 2 will look at some of the issues of population growth and rebalancing.

A Population Rebalancing Select Committee has been established by Tynwald to recognise both the Island’s demographic challenges and the long-term implications of population imbalance and to come up with workable solutions and recommendations before the end of the year. Quite separately, one of the ‘policy pillars’ within the Economic Strategy prepared by KMPG also focuses on population and proposes efforts to grow the Island’s population to 100,000 by 2037. Tynwald is scheduled to debate these economic and population proposals in November this year.

The challenges of launching a successful population policy should not be underestimated. The Island is far from unique in having an ageing population, outmigration of young adult and declining births and the solutions will necessarily cover a wide area of social and economic development.

Population rebalancing… and growth

It might be possible to grow the population of the Isle of Man without rebalancing the Island’s demographics. A drive to encourage retirement migration, for example, might do just that. This might provide a boost to the economy in some of the ways outlined above but it could make a negative contribute to the aim in the Island Plan to ‘build great communities’. It is so important here that the economy serves the population, not that the population serves the economy. At the same time, the scale of the population imbalances affecting the Island's communities are such that they cannot be mitigated without greater retention of our own young people and an influx of working adults under 50 years.

If Tynwald commits to population growth, it is vital that this growth both influences migration to reduce the age imbalance and stem the net loss of 20-29 year olds and also reverses the decline in the number of births.

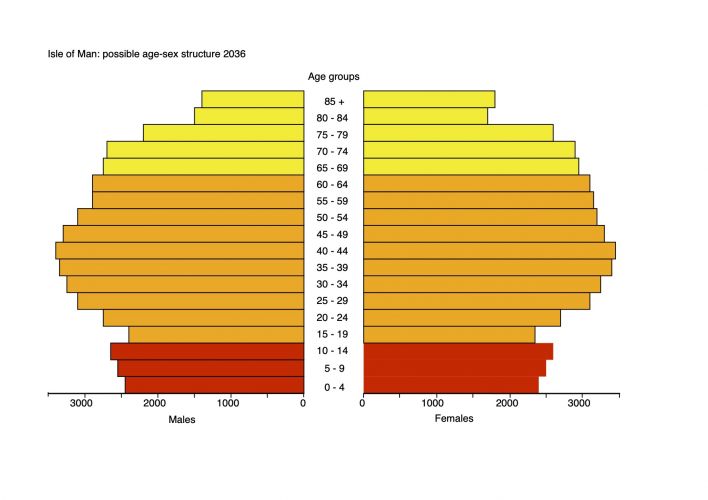

The profile below is neither a forecast nor an estimate. There are no data trends or algorithms that can be used here as the movement from the flatlining of recent years into population growth actually requires a shift away from recent trends. The profile is perhaps more conjecture than a projection as it has been prepared to offer an idea of what a population of almost 100,000 might look like - indeed, what it needs to look like to create a sustainable population going forward. It will provide a starting point for debate and actions. I have prepared the profile for the census year of 2036, rather than the target year of 2037, and I have worked on the basis of a population of several hundred lower than the 100,000 target to allow for growth in the final year.

Constructing what the 2036 profile might look like, has involved taking several factors into account including the starting (2021) population, the level and age-profile of migration to and from the Island between 2016 and 2021 and the levels of mortality for different age groups, (using comparable UK data). The low number of births in recent years now appear as the narrow 15-19 cohort. The dominant factor, however, has inevitably been the need to portray an outcome of a more balanced population approaching 100,000 in size.

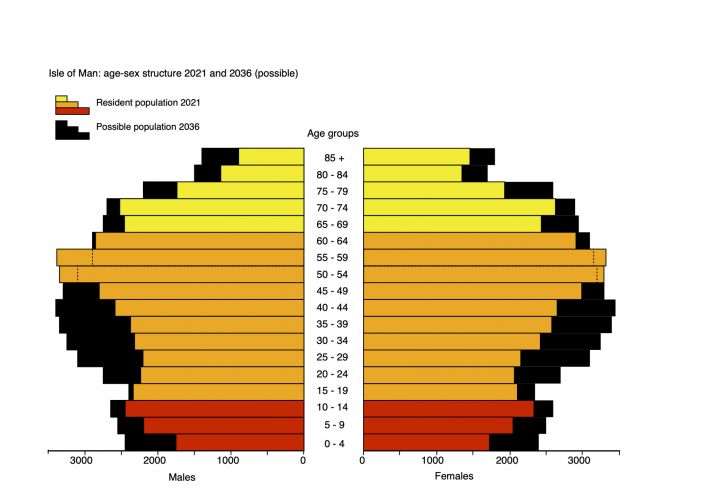

The second profile allows a comparison between the 2021 and possible 2036 profiles and shows what would need to be achieved to reach a population approaching 100,000 in 15 years. The base of the 2036 profile allows that births would need to increase to 900 per year and net migration gains of over 200 per year in the 0-14 age group have to be achieved. In the younger working age groups there is recognition that greater retention of young adults in the 15-29 age group is needed. Between 2016 and 2021 almost a third of immigrants to the Island were aged between 30 and 44 years and the profile has an expectation that this age group will continue to lead with net migration gains of around 400 per year. In the 45-59 age group there is an assumption that net migration gains slow to around 300 per year partially offset by higher mortality perhaps producing 500 deaths in this age group over a 15 year period. The profile recognises that the large 50-64 years age groups of 2021 will move up the profile and be replaced by small cohorts. Above the age of sixty there is an expectation that net immigration will continue to slow down whilst mortality rises sharply with age. The population aged over 65 years will grow in number but only by a small percentage.

The figure of 100,000 is not any sort of optimum for the Isle of Man and for most of the 40+ years that I have been studying the Island’s population I would have been very concerned by such a target. But the Island's population is showing extreme vulnerabilities due to ageing, net emigration of young adults and declines in both the number of women of child-bearing age and the number of births. These vulnerabilities present a significant challenge that will not be resolved by intervention in a single area or by small scale initiatives. A policy of steady growth at around 1,000 per year (only slightly higher than the growth of nearly 900 per year between 2006 and 2011) might be an appropriate part of such a policy. It would also appear to be achievable if a range of barriers such as housing costs and child care costs can be reduced or removed.